Blog 9: My Summer of Wills

By Sophie Erschen

I first learnt of the VOICES project when Professor Jane Ohlmeyer, our Principal Investigator, held a guest lecture at my home university, the University of Vienna, in March 2025. I was immediately intrigued by this effort to identify marginalised perspectives in historical sources and spontaneously asked Jane if I could join the team as an intern for the summer. To my own surprise, she was not only open to the idea, but extremely supportive from the get-go. A few months and administrative hurdles later, I embarked on my journey to Ireland with the help of Jane, Anne English, our wonderful team manager, and an Erasmus+ stipend.

Upon arrival, I joined the team working with wills. Throughout my time with VOICES, I had the opportunity to explore a wide range of sources, from online and hardcopy local history journals to 17th and early 18th century will books in the National Archives of Ireland. Looking for women’s wills from early modern Ireland presents a challenge: Not only was this a very tumultuous period in which wills might have been lost or simply not recorded, the 1922 fire in the Irish Public Record Office would have destroyed much of what had been preserved until then. This means that we are largely reliant on private or local collections, transcripts and summaries made before the fire as well as foreign collections, in other words, previous generations of historians of all creeds. This dependence brings with it the risk of introducing bias at the best of times. It proves to be particularly challenging when it comes to historically marginalised voices, as they would often have been filtered out rather than preserved. Thus, earlier historians often play the double role of indispensable ally and nerve-wracking obstacle.

VOICES is using digital humanities tools and modern technologies to make the most of what we do find. The results are precious, as they reveal the oft-neglected side of the story of Early Modern Ireland. A will in particular can tell us much about the woman who authored it. What she left to whom, her choice of executor or executrix and the conditions she set for the inheritance all shed light not only on her socio-economic position within her family and wider society, but also her personal network, personality and agency.

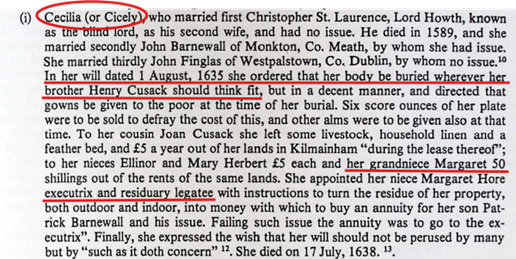

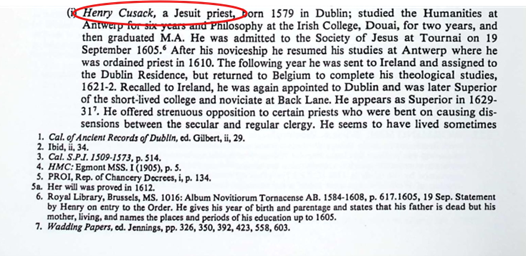

One such woman is Cecilia or Cicely Cusack. She shows up in a 1977 article in The Irish Genealogist on her family, which includes information on her funeral entry as well as an earlier abstract of her 1635 will. It is noteworthy that most of her beneficiaries are female relatives and that she selected a niece as executrix despite having at least one living son. This is not unheard of but not very common either, highlighting her agency. She is also of interest as there is information pointing to Cecilia possibly having been Catholic. In her will, she stipulated that her brother Henry should determine the specifics of her burial. Said Henry was a Jesuit priest, making it unlikely that Cecilia would ask for such a thing were she a Protestant. This is valuable information for a period in which a Catholic denomination would usually be hidden. As such, contextual information is often crucial and not always as easily accessible, adding a little detective work to the research process. In light of all of this, we can only hope that Cecilia would agree that almost 400 years later, her will and indeed her voice do concern all of us today.

Hubert Gallwey, ‘The Cusack Family of Counties Meath and Dublin. Part III Cusack of Cushinstown continued. The Cadet Branches of Dublin and Trubley. Cusack of Dublin’. In: The Irish Genealogist, Vol.5: No.4, 1977, pp.464-470.