Blog 8: Signed with her mark: Women’s wills in local history journals

By Ella Mae Cromie

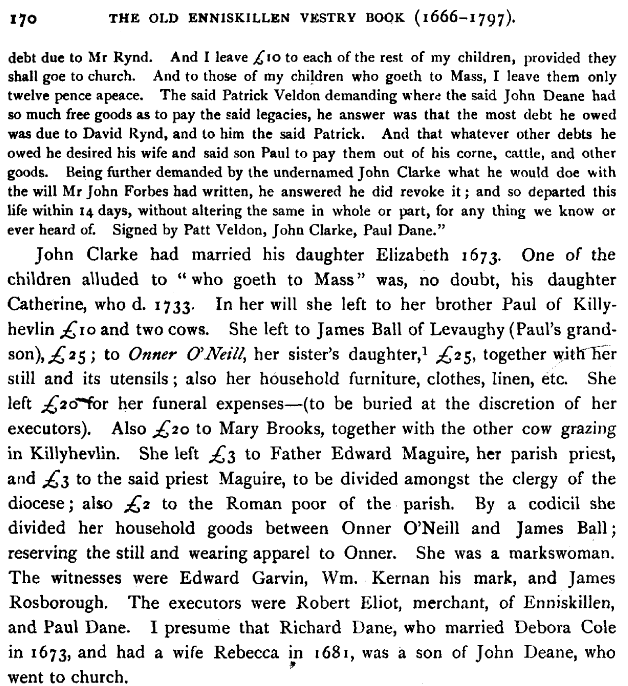

In 1733, Catherine Deane left £2 to ‘the roman poor of the parish’ and £6 to her parish priests in her will (1). Fifty-five years before writing her final bequest, Catherine had been left just twelve pence in her father’s will, on account of her attending Mass. Catherine’s protestant siblings received £10. From these two wills, we begin to piece together details of Catherine’s life. She was from Fermanagh. She was unmarried. She was the daughter of John Deane, a protestant churchwarden. These initial details converge and weave together, illuminating more about the woman behind this will. She left her personal possessions to her nieces and nephews, cows and linen and furniture. She defied her father’s wishes by keeping her Catholic faith yet remained involved in her family. She was likely illiterate, signing her will with a mark.

Catherine is just one of the early modern women I have had the privilege of encountering, since joining the VOICES project in February. It has been exciting to work on a research team that is using cutting edge technology to recover the lives of women in the early modern period. I have been primarily working on digitised copies of local history journals to find early modern wills that have been transcribed or summarised in articles. The wider team is using algorithms to extract female names from lists of thousands of individuals, asking AI to identify events in a text and implementing programmes like Transkribus to decipher fragmented manuscripts. These technologies allow us to scale up the work, uncovering many more women’s names and stories than would simply be possible by hand.

Working on this project has shown me firsthand how ethical and informed use of AI can be employed in academic research. I’ve been present at meetings and conferences where interesting discussions are taking place about how to achieve this. I’ve personally checked AI’s analysis of documents, marvelling at its speed but interrogating its findings too.

This experience has shown me the importance technological advancement in the humanities. I found Catherine’s will in a journal article originally published in 1903 but available online. Articles like this, published before the Public Record Office fire in 1922 in which countless valuable documents were destroyed, offer us a chance to rebuild our past. Without the digitisation of these local history journals, sources like this three-hundred-year-old will would be lost. Catherine Deane was all but written out of her father’s will but still left her mark on her own. VOICES is working to ensure Catherine, and the stories of other women like her, will be written back into history.

Earl of Belmore, ‘The Old Enniskillen Vestry Book (1666-1797). With Some Notes from the Parish Registers of St. Michan’s, Dublin, and of Derryvullan’, Ulster Journal of Archaeology, Special Vol. 1903, p. 170

- Earl of Belmore, ‘The Old Enniskillen Vestry Book (1666-1797). With Some Notes from the Parish Registers of St. Michan’s, Dublin, and of Derryvullan’, Ulster Journal of Archaeology, Special Vol. 1903, p. 170