Blog 7: From Handwritten Funeral Entries to Machine-Readable Texts – An internship opportunity using Transkribus to perform HTR

By Robin Dresel

With increasing digitisation, more content becomes available to be processed through computational means. Regardless of how expansive the information on the internet is, a large amount of knowledge is still only available in print. This means that researchers must manually read through every piece of information and critically assess its value for the relevance to their research.

One aim of the VOICES project is to bring together disparate texts from various sources to distil meaning across and uncover hidden connections between the manuscripts. To achieve this, making the materials available in machine-readable form reduces the time taken and increases the project’s scalability.

As a student in Digital Humanities, this became the focus of my three-month internship, which I was allowed to spend with the team, gaining insights into working with a multi-disciplinary team of researchers. It was a fascinating time, observing how computational means could assist with uncovering the past. At the same time I found it exciting to learn about the complexities in areas such as data modeling. My focus however would be on transforming the Funeral Entries supplied by the National Library of Ireland (NLI) with the help of a Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR) tool, called Transkribus.

Transkribus is a tool that uses Artificial Intelligence (AI) to perform HTR. It provides researchers with numerous AI models to choose from for the transcription process based on the respective underlying handwriting. The aim is then to utilise this tool to automate the creation of machine-readable texts from image files of the handwritten originals, thereby supporting further processing with the fewest errors.

One of the sources for the VOICES project are Funeral Entries, held by the National Library of Ireland (NLI) and made available as digitised images through a web viewer. These images were made available to the project team for transformation, and my focus was to transcribe as many as possible with the least number of errors within the internship timeframe.

To achieve the best possible outcome, we broke down the process into several steps. The primary objective was to determine the most effective AI model. For this, we ran a sample set of Funeral Entries through a handful of highly rated models and manually reviewed the results. While we counted the number of errors against the source text, we also noted the importance of accuracy for key words such as names to be higher than for other words in the text based on the nature of the project.

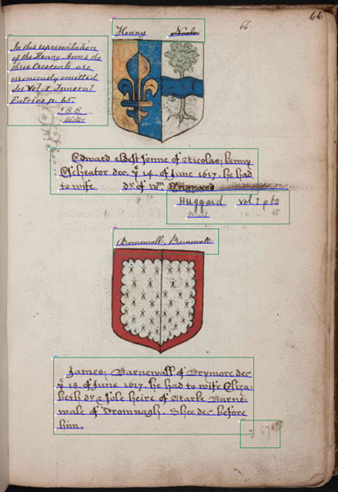

Once we had identified the model to use, I developed a step-by-step guide that would enable a new user to follow the steps taken and address the various forms a Funeral Entry could take, ensuring uniform output. This was specifically relevant as the output from Transkribus was an XML feed that would be exported and transformed into a CSV file for further processing in the project. The work, therefore, was straddling humanities and computer science, finding a balance between the constraints of the latter while maintaining the most suitable outcome from a historian’s perspective. We established the basic structure for a Funeral Entry and, from there, developed variations that could appear in the Volumes. An approach was set up to mark up the regions in Transkribus to minimally identify a header and a content portion, which would then later be extracted to form a tabular entry in the machine-readable form. Additional information, such as marginalia, would be identified where available and extracted in a separate field.

Sample funeral entry with markup for title, paragraph and marginalia by kind permission of the National Library of Ireland

Once we had established the process, we started to employ the steps we had devised. First, however, we had to transform the image files received, which came as TIFF files. For Transkribus to process those images, we had to convert them into JPG files and change the name label to reflect both the Folio as well as Transkribus’ structure. Where two pages were in one image, the image was split into two to allow for accurate referencing later.

We uploaded the resulting images into the HTR tool and marked up the regions according to our guide before running the transcription process. Within the three months of my internship this way we managed to prepare and transform about 1,500 entries, with several hundred more files prepared for upload and transformation. Finding the right tool and establishing the best process was a rewarding task, bringing both humanities and computer science together to produce a scalable, useful output for the project while exploring the marvellous handwritten sources from the past with, at times, intricate and colourful drawings.