Blog 2: Uncovering women’s voices: Testamentary records and the art of ‘dying well’ in early modern Ireland

By Dr Bronagh McShane

Death and dying are an inevitable part of life and for individuals who lived during the early modern period, the art of ‘dying well’ was of central importance. This was true for those from both Catholic and Protestant religious traditions, though the specific practices and theological emphases varied. A key element of preparedness for death was the scripting of a will. As part of my work for the VOICES project, I have been focussing on gathering testamentary records such as wills in order to probe questions about the lives and experiences of women in sixteenth and seventeenth-century Ireland. This is not a straightforward task, however. Testamentary records for early modern Ireland can be described as the epitome of an archive ‘dispersed’.(1) Unlike some of the other major archival collections that the VOICES project will engage with, such as the Irish Court of Chancery pleadings and the 1641 Depositions, which are housed together as one large collection, testamentary records are by contrast highly fragmented, widely dispersed across multiple archives and in many cases no longer extant. (2) In England, large numbers of original testamentary sources survive for the sixteenth and seventeenth century, and have informed (and continue to inform) important large-scale social and cultural studies, but the same cannot be said for Ireland. (3)

The destruction of the Irish Public Records Office in 1922 resulted in the loss of virtually all original wills proved before the local consistorial courts and the Prerogative Court of Armagh. As a result, historians of early modern Ireland are compelled to rely largely on abstracts and copies of original wills made by nineteenth century antiquarians and genealogists (which present their own challenges, especially when it comes to reconstructing the lives of women). However, one important corpus of original wills survive and are now held in TNA Kew:

wills proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury (PCC) in London include a corpus made by women (mostly of English, Protestant background) who spent part of their lives in Ireland but who also held property in England. Although small in number (c.57 for the period 1623-1720), and reflective mostly of the New English Protestant community in Ireland, the wills in the PCC collection are the single largest surviving collection of original wills made by women who lived in seventeenth century Ireland. They are of intrinsic value, offering valuable glimpses into the social, material and economic world of the female testatrixes. Importantly, they demonstrate the inherent connectedness of early modern Ireland with its nearest neighbour, revealing the frequent movement of these women and their ‘things’ across the Irish Sea.

The PCC wills demonstrate how these women prepared for death, stipulating in many cases detailed instructions on where they wished to be buried, and who was to take charge of the arrangements. Thus, in 1639, Jane Pickeman, a widow residing at Saint Patrick’s Close in Dublin city, requested that she be buried ‘neare unto my lovinge husband John Pickeman Esq[ui]r[e] deceased’. (4) Similar requests for burial next to a deceased spouse were made by Hester Whitfield of Dublin, widow of Henry Whitfield (1619-88), and Isabelle Walker, wife of George Walker (c.1643-90) of Donoughmore in Co. Tyrone. (5) In March 1667, Elinor Bladen of Dublin was even more proscriptive, stating that she wished to ‘be buried under the grave stone of her late husband in St Werburgh’s church’, adding the additional provision that one ‘Rigbey’, a minister in St Katherine’s parish church in Dublin city should ‘preach my funerall Sermon’. (6) By contrast, Dame Elizabeth Barker of County Dublin, requested that she may be ‘buryed without any pompe and with as little charge as possible with only necessary decency [and] noe Sermon’. (7)

Making arrangements for death also included the procurement of material items necessary for the ritual of mourning. Thus, several female testatrixes sought to ensure that their family members would be appropriately attired by bequeathing ‘mourning’ regalia. This was true in the case of Jane Fowke, a spinster residing in the parish of St Nicholas Within in Dublin city. In her will composed in January 1681, Fowkes stipulated that ‘the new mourning hoods and other things which lately were brought out of England for me’ would be given to one ‘Mrs Elizabeth the sister of Arthur Bush … desiring her to weare the same as mourning for me’. (8) Similarly, Mary Barry, a widow of Rathcormac in County Cork, bequeathed £5 to her cousin, ‘to buy her mo[u]rning item’. (9) Conscious of the central role played by pallbearers in transporting her body, Isabelle Walker of Tyrone bequeathed ‘six scarfes to the Bearers of my Body’. (10)

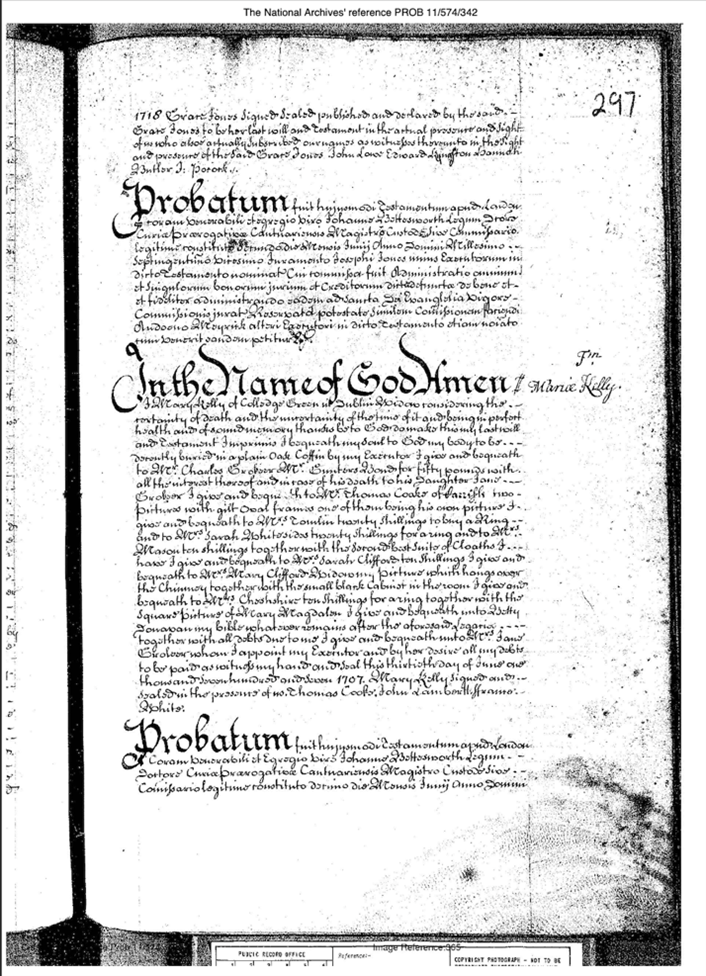

In some cases, women left specific directions about the type of coffin they wished to be interred in. Thus, in 1707, Mary Kelly, a widow of College Green in Dublin, directed that she should be ‘decently buried in a plain oak Coffin’. (11)

The examples above illustrate the potential of the PCC wills for revealing insights into these women’s preparedness for death. But they also shed valuable light on their lives, revealing how they understood their place in the world. They provide glimpse into the familial, social and friendship networks of the women in question and the bonds of affection that existed between them and their loved ones. As my research on testamentary collections continues, I hope to share more insights from the ‘Irish’ PCC wills, and other records, in follow up blogs.

Dr Bronagh Ann McShane, Research Fellow in History

- Mary O’Dowd, pioneer of early modern women’s history in Ireland, characterises the fragmentary nature of surviving sources for Irish social history as ‘the dispersed archive’. Mary O’Dowd, ‘Men, women, children and the family, 1550–1730’ in Jane Ohlmeyer (ed.), The Cambridge history of Ireland: ii, 1550–1730 (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2018), pp 299‒300.

- For a detailed discussion of testamentary sources for early modern Ireland see Clodagh Tait, ‘Writing the social and cultural history of Ireland, 1550-1660: wills as example and inspiration’ in Sarah Covington, Vincent P. Carey and Valerie McGowan-Doyle (eds.), Early modern Ireland. New sources, methods and perspectives (Routledge: Abingdon, 2019), pp. 27-48; Clodagh Tait, ‘“As legacie upon my soule”: The wills of the Irish Catholic community, c.1550-c.1660’ in Robert Armstrong and Tadhg Ó Hannracháin (eds.), Communities in early modern Ireland (Fourt Courts Press: Dublin, 2006), pp. 179-98.

- For a major large-scale project on wills in early modern England see, ‘The Material Culture of Wills, England 1540-1790’ project, led by Jane Whittle at the University of Exeter and funded by the Leverhulme Trust (https://sites.exeter.ac.uk/materialcultureofwills/)

- Will of Jane Pickeman or Pickman, Widow of Saint Patricks Close Dublin, County Dublin, TNA PROB 11/209/301

- Will of Hester Whitfeld, Widd. of Dublin, County Dublin, TNA PROB 11/453/123; Will of Isabella Walker, Widow of Donnoughmore, County Tyrone, TNA PROB 11/489/62

- Will of Ellinor Bladen, Widow of Dublin, County Dublin, TNA PROB 11/327/252

- Will of Dame Elizabeth Barker, Wife of Dublin, County Dublin, TNA PROB 11/466/378

- Will of Jane Fowke, Spinster of Saint Nicholas Dublin, County Dublin, TNA PROB 11/370/229

- Will of Mary Barry, Widow of Rathcormac, County Cork, TNA PROB 11/574/368

- Will of Isabella Walker, Widow of Donnoughmore, County Tyrone, TNA PROB 11/489/62

- Will of Mary Kelly, Widow of Dublin, County Dublin, TNA PROB 11/574/342