Blog 10: VOICES of Brigid

Dr Claire McNulty*

Introduction

Bridgett, Briggett, Brigid, Brigitt, Brigitte: these are just some of the Brigids known to have lived in seventeenth-century Ireland. They were pregnant widows in the aftermath of the 1641 rebellion, they were rebels who stole ‘English sheep’ from gentlemen, and they were daughters who lost mothers to smallpox.

The VOICES project is currently working to uncover the lived experience of such women in early modern Ireland. During a period of intense economic, political, and cultural transformation (1550 – 1700), what role did women play and how have their experiences of social upheaval, bloody civil war and extreme trauma been documented?

Harnessing the power of AI, as well as more traditional historical approaches, sources such as the 1641 Depositions, Funeral Entries, wills, and court records (digitised but unstructured) are currently being interrogated to transform our understanding of the history of women in early modern Ireland. The project aims to utilise previously digitised, and yet relatively untapped, records such as the Funeral Entries now housed under the Genealogical Office at the National Library of Ireland. Compiled by the Ulster King of Arms across the long seventeenth century, the Funeral Entries document the names, deaths, and family networks of c. 3800 people, of whom 38-42% were women.[i] The 1641 Depositions (now TCD MSS 809-841) are a collection of witness testimonies (digitised and transcribed) recording the losses of the Protestant community during the Irish rebellion, from the loss of goods and property to crimes of assault, stripping, imprisonment, and murder by Catholic rebels.[ii] Roughly 8000 testimonies survive today across thirty-one bound volumes, totalling 19000 pages. In 958 witness testimonies, mostly Protestant women (majority of whom were widows), recorded their experience of violence in the aftermath of the rebellion.

As we celebrate St Brigid’s Day this year, we began thinking about the many women named Brigid (and the many ways their names were spelt) in sources such as the Depositions and Funeral Entries. Saint Brigid was the reputed foundress and abbess of Kildare dating to c. 450-524.[iii] Saint Brigid was well documented in the annals, saints’ lives, genealogies and literature for Ireland where she was often presented as ‘a woman of power in the early Irish church’.[iv] While the cult of Saint Brigid was said to be in decline from the mid-twentieth century onwards, the records for early modern Ireland indicate that Brigid, or Bridgett, Briggett, Bridget, Brigitt, Brigitte, was a popular name amongst Catholics and Protestants, Gaels and English. From a diversity of religious, ethnic, and social backgrounds, here are some of their stories.

* With special thanks to Jane Ohlmeyer, Felix Vanden Borre, Daniel Patterson, and the wider VOICES team for their contribution

Images of the 1641 Depositions and the Funeral Entries by kind permission of The Board of Trinity College Dublin and the National Library of Ireland respectively

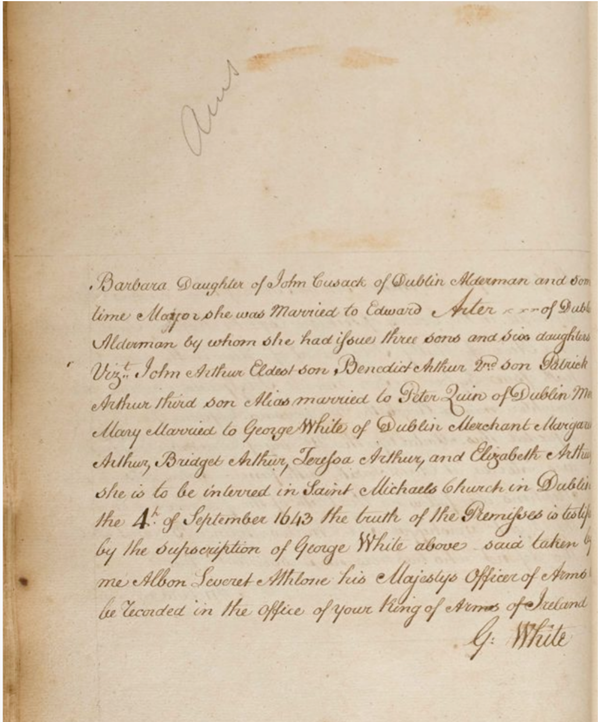

Funeral Entry Relating to Bridget Arthur

Figure 1. The Funeral Entry of Barbara Cusack in which Bridget Arthur is listed. Unusually the coat of arms relating to the Arthur/Cusacks is missing here as noted by the ‘arms’ inscription pencilled in a later hand (NLI GO MS 73 f. 88v)

Bridget Arthur was one of nine children born to Barbara Cusack and alderman (high ranking civil officer) Edward Arthur.[v] While exact family size is difficult to ascertain, evidence from the Funeral Entries will allow for a macro analysis of family structure amongst non-elite families.[vi] For each entry into the Funeral records, preliminary research suggests that there were on average at least 5 ‘mentions of’ individuals related to the deceased; however, some entries were incredibly detailed, with one in particular listing 80 individuals.[vii] The ‘mentions of’ usually included a woman’s husband, sometimes her father and mother, and oftentimes her children were included. Bridget Arthur’s mother died sometime in 1643 and was buried in Saint Michael’s Church in Dublin on 4 September 1643. According to her Funeral Entry, recorded in a careful (and perhaps later hand) by a George White, she had 3 sons and 6 daughters: John, Benedict, Patrick, Alias, Mary, Margaret, Bridget, Teresa, and Elizabeth. At the time of her mother’s recorded death, Bridget, along with her sisters Teresa and Elizabeth were noted by their maiden names.

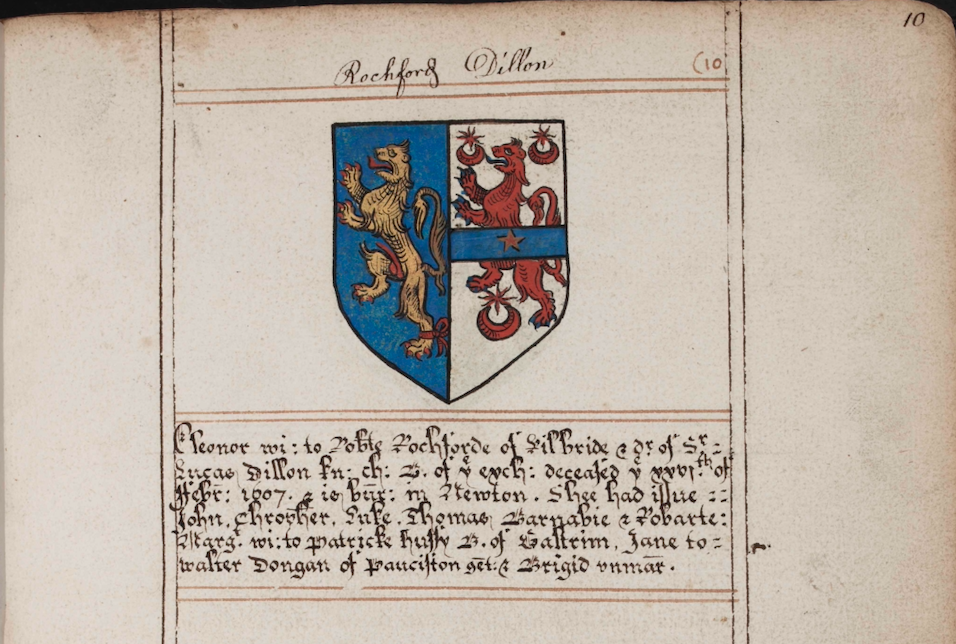

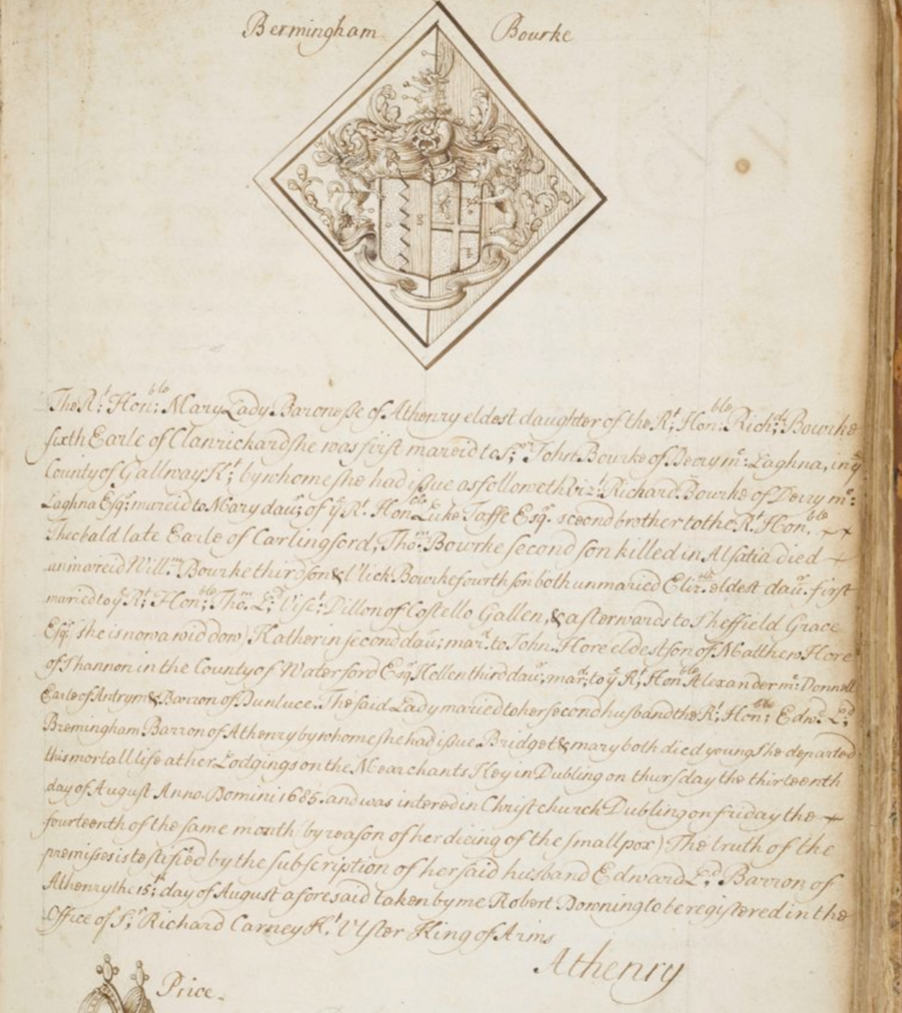

Funeral Entry Relating to Bridget Bermingham

Figure 2. The detailed Funeral Entry relating to Lady Mary Bourke whose daughter Bridget died young (NLI GO MS 76 f. 253r)

While Bridget Arthur’s mother might have died of old age, given the marital status of six of her children, the mother of Bridget Bermingham died from smallpox on Merchant’s Quay Dublin on 13 August 1685.[viii] Bridget Bermingham predeceased her mother, and although her date of death was not recorded, Bridget was said to have ‘died young’. Bridget Bermingham was the daughter of Lady Mary Bourke whose father was Richard Bourke/Burke 4th earl of Clanricarde (d. 1635).[ix] Lady Mary’s entry reads:

Bridget & Mary (her sister) both died young She (Lady Mary) departed this mortall life at her Lodgings on the Mearchants Key in Dubling on thursday the thirteenth day of August Anno Domini 1685 and was intered in Christchurch Dubling on Friday the fourteenth of the same month (by reason of her dieing of the small pox).

Outbreaks of smallpox were quite common in Dublin, ravaging the city’s population every three or four years.[x] Children appear to have been particularly susceptible to the disease which became increasingly deadly in the seventeenth century.[xi] High rates of infant mortality pervaded across early modern Europe, particularly amongst children under the age of five.[xii] While infant mortality rates were likely class and gender related, death in childhood was not uncommon for those higher up the social ranks. Following the death of Lady Mary Bourke and her daughter Bridget, Bridget’s father remarried and his new wife gave birth to another daughter whom they also named Bridget.

To date we have come across eight women by the name Brigid in the Funeral Entries: Bridget Arthur, Bridget Bermingham, Brigid O’ Cullen, Brigid Rochford/Rochfort, Brigid Bath/Bathe, Bridget Allen, Lady Bridget Fielding, and Bridget Leake/Lake. While the Funeral Entries are often brief and formulaic, they nonetheless provide ‘fugitive sightings’ of women across the ‘dispersed archive’ about whom we would otherwise know very little.[xiii]

Deposition of Brigitt Lee

Figure 3. The capital letter ‘B’ representing the signature of Brigitt Lee in a less practiced hand than the scribe recording the deposition (TCD MS 834, ff 162r-162v)

While the Funeral Entries are sometimes brief and formulaic, the 1641 Depositions provide more detailed narratives of women such as Brigitt Lee. On 24 November 1642, a year after the rebellion first broke out, Brigitt Lee reported the losses suffered, and trauma she experienced, at the hands of the rebels.[xiv] Briggitt’s husband, Richard Lee, was murdered by ‘one Donell Mc Award a notorious rebel’, though this statement was later stricken from the deposition. According to Briggitt, her husband had been a carpenter and along with their goods and chattells, the rebels had also ‘dispoyled’ their ‘working tooles’ worth £10. Further to the loss of goods, Briggitt suffered the trauma of witnessing her husband’s murder, informing the Commission that her husband had ‘in his owne defence killed 5 of the Rebells’. Briggitt reported that despite her husband’s efforts, the ‘rest of the rebells mangled and hewd (to strike with a cutting weapon) him in peeces’.[xv] Moreover Briggitt also reported the murder of Richard Blany, a knight of the shire, leaving his ‘carcass lying dead vpon a dunghill where he it lay Rotting for a whole quarter of a yeare att least’. When Christopher Watson buried Blany, the rebels threatened to hang him for treason. The depositions could be understood as trauma narratives, with scholars such as Naomi McArevey and Jane Ohlmeyer highlighting that the act of providing a deposition may have informed the process by which victims came to terms with their traumatic experiences, and viewed in this light allows us to examine the psychological impact of war in the 1640s in Ireland, and beyond.[xvi]

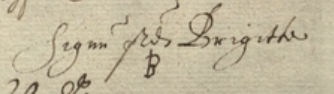

Deposition of Briggett Drewrie

Figure 4. A small capital letter ‘B’ marking Briggett Drewie’s signature to her deposition (TCD MS 836 ff 46r-46v)

On 30 June 1642 Briggett Drewrie recounted her experience of the 1641 rebellion. At the hands of the rebels, she was left a pregnant widow: ‘being left in that miserable state & predicament great with chyld’.[xvii]

Drewrie informed the Commission that she and her husband, Nicholas Drewrie, had been forcibly expelled and driven from their farm by the rebels. According to her testimony, they ‘were most Inhumanely stript of all their clothes’. Stripping, which could be considered an act of sexual violence in and of itself, featured commonly in the Depositions, with insurgents stripping more than one quarter of women as they searched for valuables hidden in clothes, shoes, and hair.[xviii] Briggett and Nicholas Drewrie were turned out into the cold and open air during one of the coldest winters on record, during which many, such as Nicholas Drewrie, died of exposure.[xix] As her husband ‘most Lamentably djed’, she was left ‘in that miserable state & predicament great with chyld’.

Drewrie was ‘of means’: married to a gentleman with whom she leased a farm spanning 200 acres in Crewcatt in County Armagh. She estimated before the Commission that the land was worth 100 marks per annum in rents and charges. A recent widow, presumably now head of household and responsible for an expansive piece of farmland, Drewrie informed the commissioners that ‘she (emphasis my own) hathe already lost & is like to be deprived of the proffitts’ until peace was established. The rebels had despoiled 100 pounds worth of corn in the ground, 60 pounds worth of oxen and cattle, 6 horses and 20 English sheep, and a trunk worth 100 pounds in clothes and fine linen. She estimated that ‘her whole present Losse’ amounted to £606 13 shillings and 4 pence. The introduction of coverture under English Common Law stipulated that a married woman was legally dependent upon her husband, her wealth subsumed with that of her husbands. The VOICES project, however, highlights the various ways in which women such as Drewrie used periods of violence and warfare to challenge patriarchal norms and advance their roles.

While women were indeed victims of violence and sexual assault (not always captured by modern terminology but referred to via euphemisms), some appear to have participated in theft and violence during the Irish rebellion.

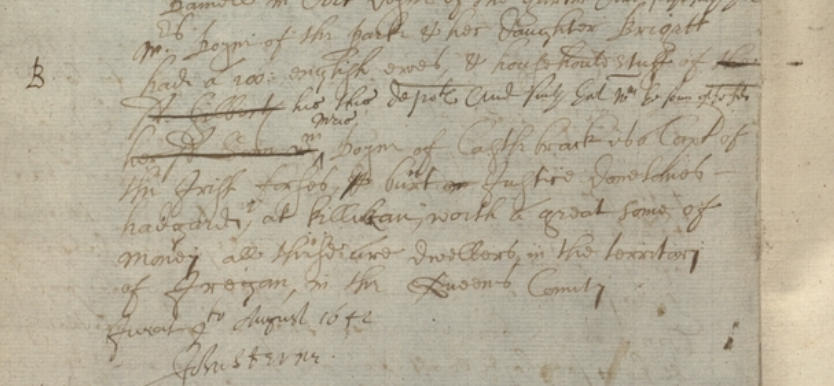

Deposition relating to Brigitt Doyne

Figure 5. Deposition of Gilbert Tarlton recounting his losses including 100 English sheep stolen by Brigitt Doyne and her mother (TCD MS 815 ff 268r-269v)

Brigitt Doyne and her mother Mrs Doyne of Castlebrack stole ‘100 English ewes & household stuff’ according to the Deposition of Gilbert Tarlton of Moniquid in County Laois.[xx] He deposed that the rebels had ‘deprived robbed or otherwise dispoyled’ several of his farms across Laois and Offaly. As well as pillaging cattle, horses, hay, and corn, the rebels robbed £355 worth of sheep – of which, Brigitt and her mother had taken 100 English ewes, as well as undisclosed ‘household stuff’.[xxi] While women such as Doyne participated, and were perhaps beneficiaries of popular uprisings, the overall experience was likely less positive.

Conclusion

Women named Brigid, spelt in its various iterations, appear across the records for early modern Ireland, from wealthy widows to wives of carpenters. In a period of intense upheaval, and against the backdrop of everyday struggles, some women assumed responsibility of large estates, even referring to losses suffered in singular personal terms, they witnessed great trauma, and they were opportunistic – using moments of disorder to advance their own circumstances, though likely losing more than they gained. By reading sources, often by the male elite, against the grain, the voices and actions of women, such as Brigid, comes to light.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

The 1641 Depositions (TCD MSS 809-841)

Funeral Entries: Armorial and Genealogical Notes made by Officers of Arms Concerning Deceased Persons and their Funerals (NLI GO MSS 64-78)

Select Secondary Sources

Clarke, Aidan, ‘The 1641 Depositions’ in P. Fox (ed.), Treasures of the Library, Trinity College Dublin (Dublin, 1986), pp 111-122

Kissane, Noel, Brigit (Brighid, Bríd, Bride, Bridget), Dictionary of Irish Biography

MacCurtain, Margaret and Donnchadh Ó Corráin, Women in Irish Society: The Historical Dimension (Dublin, 1978)

MacCurtain, Margaret, Mary O’Dowd and Maria Luddy, ‘An Agenda for Women’s History in Ireland, 1500-1900’, Irish Historical Studies, vol. 28 (1992), pp 1-37

MacCurtain, Margaret and Mary O’Dowd (eds), Women in Early Modern Ireland (Edinburgh, 1991)

McAreavey, Naomi, ‘Re(-)Membering Women: Protestant Women’s Victim Testimonies during the Irish Rising of 1641′, Journal of the Northern Renaissance (2010)

McKenna, Lucy, Bronagh Ann McShane, Jane Ohlmeyer, Declan O’Sullivan, and Daniel Patterson, ‘Digital Humanities and AI in Women’s History: The VOICES Project (Ireland)’ (forthcoming)

Nolan, Frances, and Bronagh McShane, ‘Introduction: A New Agenda for Women’s and Gender History in Ireland’, Irish Historical Studies, vol. 46 (2022), pp 207-216

O’ Dowd, Mary, History of Women in Ireland, 1500-1800 (Edinburgh, 2005)

Ohlmeyer, Jane, Viragoes and Matrons. The Lived Experiences of Women in Seventeenth-Century Dublin (Dublin, 2025)

Forthcoming, ‘Women and Sexual Violence in the “1641 Depositions”‘, Law and History Review (2025), vol. 43, pp 221-238

Forthcoming, Making Empire: Ireland, Imperialism, & the Early Modern World (Oxford, 2023)

Tait, Clodagh, ‘Progress, Challenges and Opportunities in Early Modern Gender History, c.1550–1720’, Irish Historical Studies, vol. 46 (2022), pp 244–269

[i] Lucy McKenna, Bronagh Ann McShane, Jane Ohlmeyer, Declan O’Sullivan, and Daniel Patterson, ‘Digital Humanities and AI in Women’s History: The VOICES Project’ (forthcoming).

[ii] Jane Ohlmeyer, ‘Women and Sexual Violence in the “1641 Depositions”‘, Law and History Review (2025), vol. 43, pp 221-238, (p. 222).

[iii] Noel Kissane, Brigit (Brighid, Bríd, Bride, Bridget), Dictionary of Irish Biography (2009) https://doi.org/10.3318/dib.000961.v1

[iv] Mary O’Dowd, ‘Margaret MacCurtain (1929–2020): An Appreciation’, Irish Historical Studies (2022), pp 217-223, (p. 220).

[v] NLI GO MS 73 f. 88v.

[vi] While S.J. Connolly estimated a high 6.4 infants born to women in the British and Irish peerages, this number may differ for non-elites, see, S.J. Connolly, ‘Family, Love, and Marriage’ in Margaret MacCurtain and Mary O’Dowd (eds), Women in Early Modern Ireland (Edinburgh, 1991), pp 276-290, (p. 285).

[vii] Many thanks to Felix Vanden Borre for his research on the Funeral Entries and for his insights here.

[viii] NLI GO MS 76 f. 253r.

[ix] Colm Lennon, ‘Burke, Richard, Fourth Earl of Clanricarde and First Earl of St Albans’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004) https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/67043

[x] Jane Ohlmeyer, Viragoes and Matrons. The Lived Experiences of Women in Seventeenth-Century Dublin (Dublin, 2025), p. 13.

[xi] Clodagh Tait, ‘Some Sources for the Study of Infant and Maternal Mortality in Later Seventeenth-Century Ireland’, in Elaine Farrell (ed.), ‘She Said She Was in the Family’: Pregnancy and Infancy in Modern Ireland (London, 2012), pp 69– 72.

[xii] Connolly, ‘Family, Love, and Marriage’, p. 285.

[xiii] Mary O’Dowd, ‘Men, Women, Children and the Family, 1550–1730’ in Jane Ohlmeyer (ed.), The Cambridge History of Ireland: ii, 1550–1730 (Cambridge, 2018), pp 299‒300; Patricia Palmer, ‘Fugitive Identities: Selves, Narratives and Disregarded Lives in Early Modern Ireland’ in Eve Campbell, Elizabeth Fitzpatrick and Audrey Horning (eds), Becoming and Belonging in Ireland, A.D. c.1200–1600 (Cork, 2018), pp 313‒27.

[xiv] TCD MS 834, ff 162r-162v.

[xv] TCD MS 834, ff 162r-162v; ‘Hewd’ as defined in the OED.

[xvi] Ohlmeyer, ‘Women and Sexual Violence’, p. 232; Naomi McAreavey, ‘Re(-)Membering Women: Protestant Women’s Victim Testimonies during the Irish Rising of 1641′, Journal of the Northern Renaissance (2010).

[xvii] TCD MS 836 ff 46r-46v.

[xviii] Ohlmeyer, ‘Women and Sexual Violence’, pp 227-228.

[xix] Ibid, p. 227.

[xx] TCD MS 815 ff 268r-269v

[xxi] Brigitt’s brother, William Doyne, was named as captain of the Irish forces and was said to have ‘burnt Justice Donelanes’.