Blog 3: From the ashes: Locating women in Irish Chancery Court records

By Dr Daniel Patterson

Writing about medieval and early modern Irish history almost invariably refers, in one way or another, to the inestimable losses incurred by the 1922 destruction of the Public Record Office of Ireland. The challenge which the destruction of Ireland’s records presents for its historians is hard to overstate. Introductions and conclusions framing Irish historical writing often include provisos that certain matters must remain shrouded in obscurity. Women, as subjects of historical analysis, too often fall victim to this kind of rhetoric: we don’t have much to say about Irish women, because the sources that mentioned them have not survived.

In recent years, however, a number of historians have begun to emphasise the importance of ‘focusing on the positive’; of developing new and imaginative ways to approach Irish history and asking new questions of different sources to write histories of women, gender, the family, and sexuality. (1)

We know very well what was lost in the fire – almost everything – but what of the documents which survived? A major strand of the VOICES project centres on perhaps the most significant collection of surviving documents formerly held in the PROI: the records of the Irish Court of Chancery.

These documents, which mostly date from the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, survived the fire in considerable numbers – though not altogether unscathed. In the aftermath of the disaster, they were plucked from the rubble and placed in paper parcels, where they remained for the rest of the twentieth century, receiving only sporadic attention from historians. (2)

The fire had left the records extremely difficult to use. Covered in soot from the fire, some were literally rotting, while others were crumbling to dust. And so, beginning in 1999, the National Archives of Ireland set out to conserve the surviving documents and render them stable and usable for researchers. To date, 5,265 documents have been painstakingly conserved, with a similar number still awaiting treatment. (3)

Surprisingly, despite the fact that thousands of Irish Chancery records are now beautifully conserved and accessible to scholars, they have yet to find their historian. No significant work has been published since Mary O’Dowd’s seminal 1999 article which highlighted Chancery as a uniquely rich resource for Irish women’s history.

What was Chancery, and why are its surviving records so uniquely appealing to historians of women? A bureaucratic extension of the personal power accorded to the Lord Chancellor, the most senior judicial officer in the land from the early thirteenth century until 1922, Chancery was the highest court of equity in Ireland. In this respect, it was a mirror image of the Court of Chancery in England, which has received much more attention from historians. (4)

Equity is a body of law which provides legal remedies based on moral reasoning and “fairness” in cases where the common law cannot provide one, or where strictly following the letter of the common law would result in a demonstrably unfair resolution. (5) This was one reason why it seems to have held special appeal as a ‘court of redress’ for women in the early modern period, who were systematically discriminated under common law due to doctrines such as coverture. (6)

Irish Chancery has therefore been identified as a key target for the VOICES project. However, tackling such a mountain of documentation (over 5000 items, poorly understood!) is a daunting prospect for any researcher. Our approach draws upon both traditional historical and cutting-edge digital research techniques to locate women in the records of Chancery. First, we used detailed catalogues created by K. W. Nicholls in the 1970s and more recently by the NAI to identify the presence of women in the archive. In order to render this a more manageable task, we elected to limit our search to lawsuits which named women as a plaintiff or defendant, or both. We compiled the resulting list of 1,212 documents into a spreadsheet.

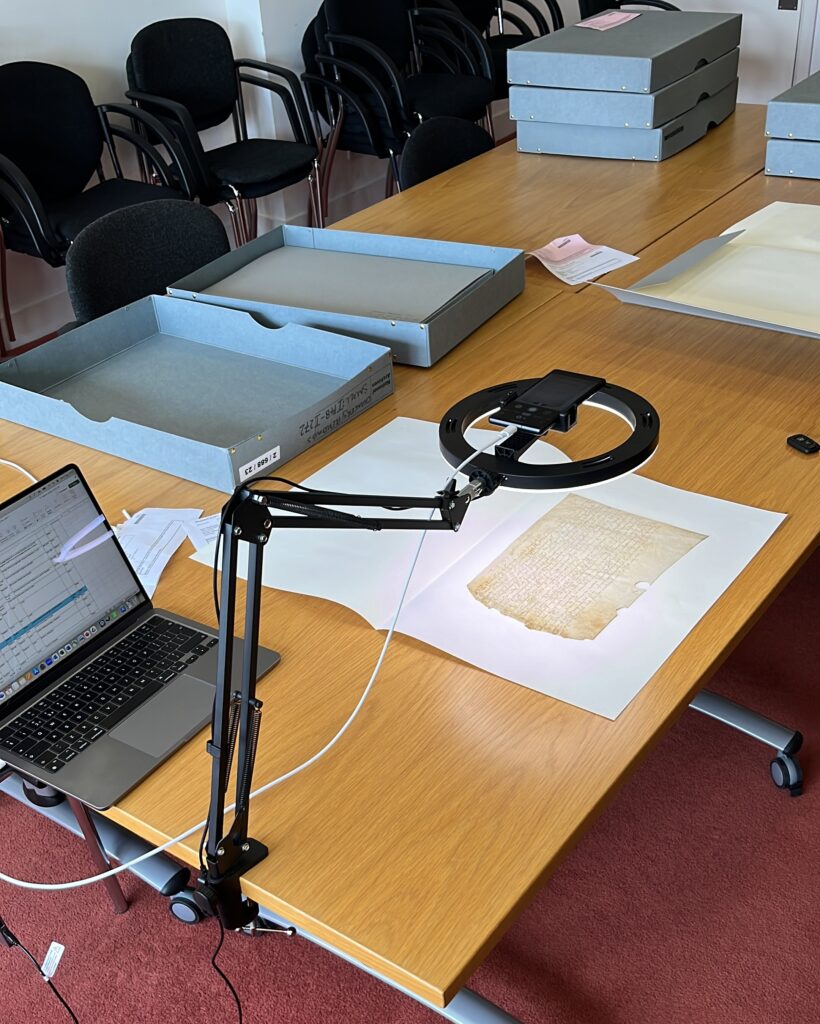

The next step was to gain access to the documents themselves. With permission from the NAI, I spent the summer of 2024 photographing over one thousand documents during weekly visits.

Figure 1: My rough and ready photography setup at NAI, with ring light and camera stand

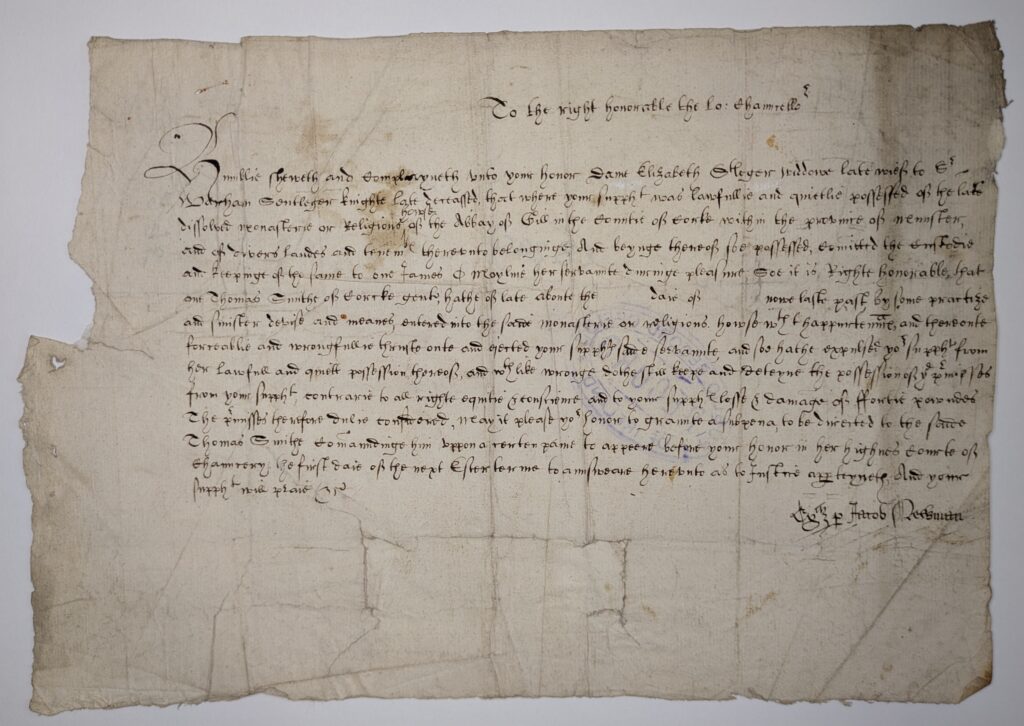

Instead of painstakingly reading over 1,212 documents and transcribing them manually, which would take months or years, VOICES will leverage innovative technology to expedite the process of interrogating the contents of the archive. Our Chancery images were therefore uploaded to cloud storage, then individually cropped, edited, and renamed according to their archival reference numbers. This was all done in preparation for processing using an AI-based digital transcription tool called Transkribus.

Figure 2: An example of a cropped and edited Chancery document, ready for Transkribus processing. NAI CP B/295

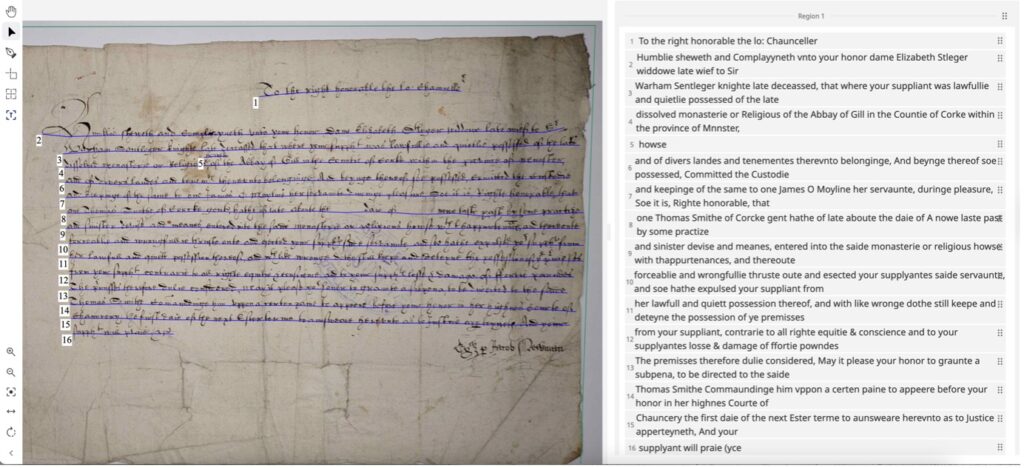

Transkribus is capable of producing highly accurate transcriptions of manuscript texts. We collaborated with Professor Emily Kadens (Northwestern University, USA), a legal scholar who has developed a dedicated Transkribus model specifically to read sixteenth-century English Chancery pleadings. Luckily, Irish Chancery pleadings are physically almost identical to their English counterparts, and so when Emily kindly permitted us to use her model to ‘read’ our texts, the outputs were of very high quality.

Figure 3: The same image following Transkribus processing. The automatic transcription (unedited) is on the right hand side

The texts generated by Transkribus are now being curated so they can be subjected to various forms of historical and quantitative analysis. In future, we also plan to extract data relating to women from the documents – their names, occupations, marital and social statuses, geographical locations, and more – for uplift to the VOICES Knowledge Graph. We will explore this process, as well as some of the fascinating stories contained in the Irish Chancery records, in a future blog. But for now, thanks for reading!

The VOICES project team would like to extend their gratitude to the staff at the National Archives of Ireland, particularly Zoë Reid and Peter Goode, without whom this work would not have been possible.

(1) M. O’Dowd, ‘Men, women, children and the family, 1550–1730’ in J. Ohlmeyer (ed.), The Cambridge history of Ireland: ii, 1550–1730 (Cambridge, 2018), p. 299; F. Nolan and B. McShane, ‘Introduction: A New Agenda for Women’s and Gender History in Ireland’, Irish Historical Studies, 46 (2022), pp. 207–16; C. Tait, ‘Progress, Challenges and Opportunities in Early Modern Gender History, c.1550–1720’, Irish Historical Studies, 46 (2022), pp. 244–69

(2) Initially by Kenneth Nicholls in the 1970s, and subsequently by Mary O’Dowd and Jane Ohlmeyer at the turn of the twenty-first century; K. W. Nicholls, ‘Some documents on Irish law and custom in the sixteenth century’ in Analecta Hibernica,6 (1970), pp. 103–29; ‘A calendar of salved Chancery Pleadings concerning County Louth’, Journal of the County Louth Archaeological and Historical Society, 17 (4) (1972), pp. 250–60; ‘A calendar of salved Chancery Pleadings concerning County Louth (continued)’, Journal of the County Louth Archaeological and Historical Society, 18 (2) (1974), pp. 112–20; M. O’Dowd, ‘Women and the Irish Chancery Court in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries’, Irish Historical Studies, 31 (124) (1999), pp. 470–87; J. Ohlmeyer, ‘Records of the Irish Court of Chancery: A preliminary report, 1627–1634’ in D. Greer and N. Dawson (eds), Mysteries and Solutions in Irish Legal History (Dublin, 2001), pp. 15–50

(3) Z. Reid and B. ven de Wetering, ‘Conservation of the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Chancery pleadings at the National Archives of Ireland’, Journal of the institute of conservation, 35 (2) (2013), pp. 189–200

(4) W. J. Jones, The Elizabethan Court of Chancery (Oxford, 1967); M. Cioni, Women and law in Elizabethan England, with particular reference to the Court of Chancery (Garland: New York, 1985); A. Capern, ‘Maternity and Justice in the Early Modern English Court of Chancery’, Journal of British Studies, 58 (2019), pp, 701-16; idem, ‘Emotions, Gender Expectations, and the Social Role of Chancery, 1550-1650’ in Authority, Gender and Emotions in Late Medieval and Early Modern England, ed. Susan Broomhill (Palgrave Macmillan: London, 2015), 187-209; A. L. Erickson, Women and property in early modern England (Routledge: London, 1995)

(5) Chancery and other equity courts, both in England and Wales and in Ireland, were abolished as part of sweeping judicial reforms in the 1870s

(6) For an excellent assessment of Chancery as a ‘court of redress’ for women in an English context, see C. Garside, Women in Chancery: An analysis of Chancery as a court of redress for women in seventeenth-century England (Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Hull, 2019)